This is the Eagle Valley power plant in Martinsville, Indiana. Its four coal-fired generators were built in the 1950s.

Back then, the generators had an expected useful life of about 30 years.

Sixty years later, they were still running.

No major source of electricity pollutes more than an old coal plant. Compared to a state-of-the-art natural gas plant, the average coal plant emits over 100 times more sulfur dioxide, five times as many nitrogen oxides, and twice as much carbon dioxide per megawatt-hour. Meanwhile, renewable sources of energy, like wind turbines and solar panels, emit no pollution at all.

A 2010 report from the Clean Air Task Force estimated that pollution from the Eagle Valley plant caused:

Each Year

And Eagle Valley isn't an anomaly. At the end of 2015, almost 300 coal-fired generators in the US had been operating for 50 years or longer.

Why are so many of these clunkers still in service? Ironically, much of the blame lies with our nation’s most important environmental law, the Clean Air Act of 1970.

Passed by a nearly unanimous Congress and signed by President Richard Nixon, the Act was remarkably ambitious: It sought to eliminate essentially all air pollution that posed a threat to public health.

But it contained a terrible flaw.

The Clean Air Act required the EPA to set stringent limits on soot- and smog-forming pollution from new industrial facilities but made existing facilities exempt.

That was a very big mistake.

The Trouble with Grandfathering

Imposing tough standards on new sources of pollution and lax or no standards on existing sources creates two problematic incentives: Old facilities are encouraged to stay in business longer than they otherwise would, and new facilities are discouraged from coming online at all.

Starting in 1971, newly constructed coal plants either had to install multimillion-dollar emission “scrubbers” or burn pricey low-sulfur coal. But utilities could avoid these costs by keeping their old plants running instead of replacing them with new ones.

Congress didn’t intend to leave old plants entirely unregulated. In addition to directly restricting pollution from new sources, the Clean Air Act required the EPA to set limits on soot and smog in the ambient air.

States had to design plans for meeting the ambient standards, and Congress figured those plans would include controls on old plants.

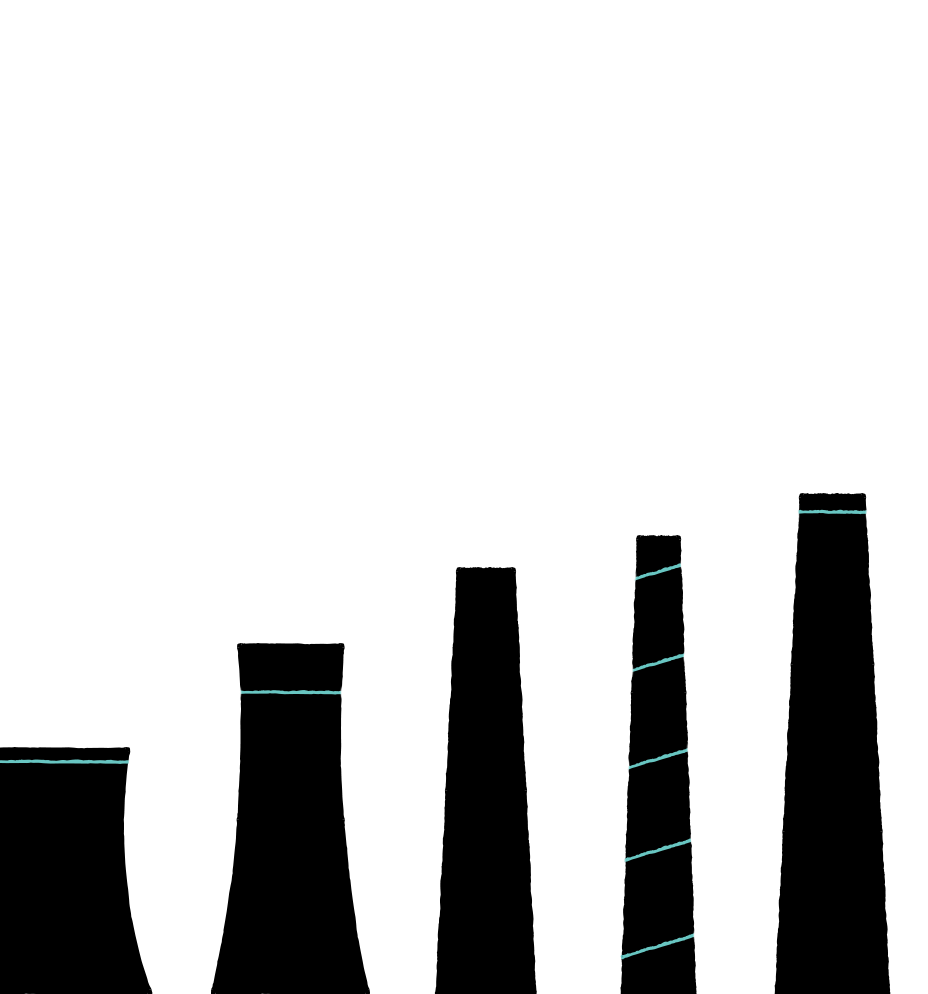

But utilities and friendly state regulators found ways to game the system. Ambient standards limit pollution near the ground, so utilities in many states simply increased the height of their plants’ smokestacks. Voilà! The air around the plants was cleaner!

In 1969, fewer than a dozen smokestacks in the US were over 500 feet tall (about the height of the Washington Monument). A decade later, that number had climbed to 180 (and all but 8 were attached to power plants).

700 feet tall

800 feet tall

Unfortunately, pollution sent higher into the atmosphere didn’t disappear. It blew into other states, where it caused new problems, like acid rain.

Under Clean Air Act rules, old plants that underwent “modification” were supposed to become subject to the same requirements as new plants. But there was an exception for “routine maintenance,” so plant owners began calling every construction project—no matter how elaborate—“routine.”

Over the years, pollution from grandfathered plants has taken a grim toll on public health, causing hundreds of thousands of premature deaths.

But these facilities might not be around much longer. By 2025, plant owners are expected to shutter the vast majority of pre-1970 generating units.

What’s driving the retirements? Policies and prices.

While the Clean Air Act still exempts old plants from nationwide limits on soot- and smog-forming pollutants, the EPA does have power to regulate the plants’ emissions of other types of pollution.

And that’s what what its two most important new rules do:

Mercury and Air Toxics Standards

These standards restrict power plants’ emissions of mercury, which can harm the developing brains of fetuses and young children, as well as other toxic metals like arsenic and chromium, which can cause cancer.

Clean Power Plan

This rule limits power plants’ emissions of carbon dioxide, the primary driver of global climate change.

Critics claim that these regulations are an unprecedented “war on coal” by the Obama administration. In fact, the rules build upon regulatory groundwork laid over three decades by Republican and Democratic administrations alike.

Just as new regulations are pushing costs up for grandfathered coal plants, record low prices for natural gas have pushed their cleaner competitors’ costs down.

Between 2008 and 2014 the price of natural gas declined by almost 45 percent, thanks in large part to the fracking boom.

In April 2015, the US generated more electricity with gas than with coal for the first time in history.

The Eagle Valley plant finally closed in April 2016, and will be replaced by a new gas-fired facility.

But there's no guarantee that all other old coal plants will follow suit. Gas may not stay cheap forever. And coal supporters are challenging the EPA’s new rules in court.

If gas prices rise more than expected or the rules are struck down, a significant number of grandfathered plants may live to pollute another day—or decade.